International Institute for Middle East and Balkan Studies (IFIMES) from Ljubljana, Slovenia, regularly analyses developments in the Middle East and the Balkans. Prof. Nedzad Korajlic, Dean of the Faculty of Criminalistics, Criminology and Security Studies, University of Sarajevo, BiH and Amer Smailbegovic, Adjunct Faculty/S.M.E. Crisis Management, Faculty of Criminology, Criminalistics and Security Studies, University of Sarajevo, BiH prepared comprehensive analysis entitled “Natural Disasters as Detonators of Socio-political Change: Bosnia-Herzegovina 2014-2020”. They are analyzing the potential of natural disaster to initiate a required social and political change in a divided society, when other methods of integration and resolution have proven ineffective.

● Prof. Nedzad Korajlic, Ph.D.,

Dean of the Faculty of Criminalistics, Criminology and Security Studies, University of Sarajevo, BiH

● Amer Smailbegovic, Ph.D.,

Adjunct Faculty / S.M.E. Crisis Management, Faculty of Criminology, Criminalistics and Security Studies, University of Sarajevo, BiH

The report ifs briefly summarizing the potential of natural disaster to initiate a required social and political change in a divided society, when other methods of integration and resolution have proven ineffective. By comparing the Balkan floods of 2014 with the current COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible to observe certain changes in the posture of the former-Yugoslavian countries and their collaboration by using the last vestiges of once-robust civil-defense (and general national defense / protection) of the former Yugoslavia. The current response is adequate, but the lengthy period of stagnation, decentralization and unresolved issues stemming from the Yugoslav conflict have left considerable present-day challenges. Similarly there were missed opportunities for improving collaboration and crisis management in the aftermath of the 2014 flooding event. The current crisis presents new management opportunities to overcome the problems and evolve the legacy solutions in the time of crisis. The reader is cautioned that this is an evolving situation, and some of the events described within, are bound to change rapidly, hence this communiqué should be considered as a snapshot in time during the pandemic-response in the Western Balkans in the second half of March, 2020.

Keywords: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Pandemic, Crisis communication, Civil Defense, Yugoslavian General National Defense and Communal Self-Protection Concept, Western Balkans cooperation.

To achieve success and ensure effective leadership and crisis resolution, it is paramount that everyone on the team (and team can be as big as the group of countries) needs to have a clear idea on what the ultimate goal is. Open communications within the participants, up to the highest level of decision making and down to the personnel on the ground creates an environment known as the “shared reality” (Blaber, 2008). Rather than keeping one’s ideas, observations, notions and plans compartmented from everyone else, they must be shared with the participating group. In order to achieve the goals, defeat the crisis and ensure success, one must continuously seek feedback (positive or negative), voice and exchange ideas, and work together to achieve a common goal. This is currently lacking.

Southern Europe has overtaken China as the main focal area of the recent COVID-10 pandemic and it is already possible, academically speaking, to look at the comparative crisis-management portfolios deployed by the various political systems. In particular, it is possible to analyze the relative effectiveness of methods aimed towards ebbing the flow of the contagion and its spread, particularly in the dense urban environments. At the time of the writing of this communiqué, the Western Balkans (and former Yugoslavian states in particular) are experiencing over 1500 confirmed cumulative cases. Montenegro, for a while, was the last remaining hold-out without any reported cases, but as of March 17, 2020, the contagion manifested there with 8 reported cases. Even otherwise slow to act, most of the states have quickly realized the challenges posed by the new threat and what it could do to their relatively modest (and in places sub-standard) medical facilities. In that regard, sets of preventive measures are fielded by the ex-Yugoslav states to slow-down the onset of full crisis and give them a manageable chance to avoid the Italian mass-casualty scenario.

Figure 1 – Current infections / fatalities from COVID-19 in former Yugoslavia; compared to that of Italy, as of March 20, 2020; the current daily increase is about 30% and expected rise in mortalities as the pandemic progresses.

The case of epidemic / pandemic is not the first wide-ranging natural disaster the Western Balkans is facing together: the floods of May 10-14, 2014 have caused considerable damage and destruction. In approximately 72 hours, three months' worth of rain had fallen in Croatia-Bosnia-Herzegovina-Serbia. The flooding was caused by an extra-tropical cyclone (Tamara) that pulled in moisture from the Mediterranean Sea for nearly three days. Much of the water has increased the water-flow of Sava River, which cuts across the middle of the Balkan Peninsula. The event is considered the region’s worst flood in more than 120 years of record-keeping (NASA EOS, 2014). More than 40 percent of Bosnia and Herzegovina was thought to be in some level of flooding. The floodwater destroyed nearly 100,000 structures and homes, killed thousands of livestock animals, and exposed or moved many landmines that were set during the 90’s conflict in Bosnia-Herzegovina. The flood-affected region was in the excess of 20,000 square kilometers and over 2 million residents have been displaced or threatened. The disaster response took an unprecedented engagement of local, regional and state-wide assets to provide immediate response, evacuation and mitigation afterwards (Huseinbasic, 2014).

Figure 2 – Extent of flood-affected regions and communities during May 10-14, 2014 flooding event (adapted from a report by Huseinbasic, 2014).

The floods have also marked a first instance of direct cooperation between the communities in the main administrative regions of Bosnia-Herzegovina. All administrative entities of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (FBIH), Republic of Srpska (RS) and District of Brcko (DB), instituted after the Dayton Peace Accords of 1995, have certain emergency-response bodies, assets and procedures, majority of them modeled after the former Yugoslav system. The emergency services operate alongside with very little coordination and cooperation. The flood of 2014 had changed that, at least unofficially, in the affected communities near the municipalities of Doboj and the District of Brcko where there were noted occurrences of cross-cooperation among the administrative regions (CCI, 2019). The analyses performed in the aftermath have noted that

…in a decentralized country such as BiH the alternative does not lie in developing two independent protection systems, but that solution lies in developing entity systems that are completely harmonized and that are functionally complemented thus making a unity, which is compatible with the systems of the countries in the region (CCI, 2019).

There was a certain impetus to improve the interoperability and cooperation of the emergency services in Bosnia-Herzegovina as a result of the flooding in 2014 (and subsequent flooding in 2019) and agency cooperation, primarily between FBIH and RS entities (European Commission, 2016), however the opportunity was squandered because of the lack of local political vision or other obstructions aimed towards continued decentralization of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Sijercic, 2018). Even though the post-conflict organization of Bosnia-Herzegovina intended and provisioned for a close cooperation of the administrative units, such practice has not been realized due to the competing visions and motives about the organization of the country. With the lack of clear hierarchy on a state-level, lack of consensus on the integrating factors (language, state symbols, educational programs) and continued secessionist tendencies (IFIMES, 2010), lately encouraged by the various types of hybrid actions (Kuczyński, 2019), it is obvious why even in the time of the crisis, it is difficult to overcome these challenges. Certain secessionist tendencies are being even carried out during the crisis, such as a controversial decision of the Canton No.10 to bar the entry to all citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina into the Canton (Zurnal, 2020) effectively seizing control of order border-crossings into the country, without prior approval from the higher levels of the Federation and State Government (in whose jurisdiction such decision resides).

The Western Balkans region is also a home to several endemic pathogens that could present potential pathways for the emerging epidemic / pandemic scenarios and crisis-response. The last known occurrence of small-pox was centered in Albania-Kosovo-Serbia region in 1972 (Ristanovic & Gligic, 2016) and required considerable national assets to contain, which in the current fragmentary nature of the Western Balkans would be quite challenging, if not impossible. Furthermore, the region is known for the endemic occurrences (Ahmeti, L., Possel, & Thome-Bouldan, 2019) of the Crimea-Congo Hemorrhagic Virus type (Kosovo and Albania), Typhus (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro) as well as occurrences of novel-types of Tuberculosis (resulting from the migrations originating in Southern Asia) or other emerging pathogens brought on by the migrations (IFRC, 2018).

Former Yugoslavia, always living in the shadow of a possible European conflagration and Soviet/Warsaw-pact invasion during the 1960’s and 1970’s had employed the concept of general preparedness called general (total) national defense and communal self-protection (Broz-Tito, 1980). This concept had instituted a heavy reliance on the local communities to consider and implement all possible scenarios related to the hostilities, as well as response during the times of national emergencies and natural calamities. Some of these basic building-blocks have been integrated into the present-day emergency-preparedness and crisis-response scenarios, particularly in Serbia-Montenegro-Kosovo-Northern Macedonia and to extent Bosnia-Herzegovina, where certain provisos of the former state’s (Yugoslavia) emergency planning remain ingrained in the present-day organization, particularly in the civil defense sector. Slovenia and Croatia have retained some of the elements, but have harmonized it with the EU / NATO directives required for their membership in those two transnational organizations. In the course of the recent events, the Western Balkan countries have implemented almost unprecedented level of coordination, communication and execution transgressing the daily political blockades and political-infighting, particularly in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Without a doubt, once COVID-19 threat is removed, there will be numerous articles examining the minutiae of the crisis and how it could have been handled. We are already witnessing some of the shortcomings arising from poor communication (USA), lack of unified goal and strategy (UK), heavy-handed tactics (China), lack of planning and preparedness (Iran), late response (Italy) and so on. The goal is not to point fingers, but to implement the lessons learned, communicate the full picture of reality on the ground and minimize the over-reaction, which can be even more counter-productive than the threat that needs to be mitigated. The current pathogen is likely to be replaced by another, possibly even more virulent and deadly strain and the lessons learned from the recent pandemic will be life-saving in the future (Johns Hopkings University, 2019). In our recent cross-institution/cross-border endeavors with NATO and Western Balkans partner entities from the government and academia, we began to develop scenarios and response-types for curbing threats originating from the Western Balkans region. The table-top discussion and exercises were intended to model the potential disaster origins, spreading pathways and types and to make determination whether it is a natural disaster or an act of terrorism (e.g. bioterrorism, attacks against water infrastructure etc.). A particular accent was given to the considerable migrant populations housed in cramped quarters with a less-than-adequate sanitation and potential spread of pathogens into the wider community (IRFC, 2018). We were intending to explore the venues in which the non-state actors could exploit biological agents to create a crisis and to develop a variety of scenarios and predictive models to resolve the crisis.

The entire territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina remains in the state of a frozen conflict, where the return to hostilities, although unlikely, is always possible and that overall situation is overprinted upon the general situation in the current crisis. The situation is similar to some other regions of frozen or simmering conflict, namely in Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine and Kosovo* from the standpoint that the central government may not have “complete” control of its borders. Twenty-five years after the cessation of hostilities, Bosnia-Herzegovina is by many key indicators a “failed-state” (as a result of various internal obstructions reinforced by the certain external factors), with a barely functioning central government and sluggish legal system, mired in a patchwork of ethnic political fiefdoms, where handful of “leaders” try to preserve their carved out possessions in a country of devolved-governance (Less, 2020). For many years EU was pushing for a mission of local ownership and local solution for the myriad of problems, however the focus on the local-level led to the further consolidation of corrupt or entrenched political clans. Given the lack of any viable alternative to challenge this self-reinforcing cycle, a disruptive element such as the current pandemic, may give at least some impetus towards reforming the society and making at least some of its elements functional or it may hasten the apparently “inevitable” break-up of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Less, 2020).

The current mass-migration crisis is in full swing in the Western Balkans since 2015, but exacerbated by the closing of the Hungarian border in 2016 and the subsequent State of Emergency still in force. The Western Balkans migration route was and still remains as an only semi-viable pathway for the massive influx of migrants from the Middle East and Africa (IRFC, 2018). According to the United Nations, 80% of the almost one million refugees that found shelter in Germany in 2015 passed through this route by either registering at the Presevo Refugee Center in Serbia (600,000) or bypassing it and moving on through Bosnia-Herzegovina, into Croatia and beyond (Cocco, 2017). The issue was further complicated by Serbia’s liberal visa regime with the several developing nations including Iran (Lakic, 2018) resulting in significant numbers (est. 23,000 since 2018) of migrants seeking to enter EU via Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia (Kalan, 2019). The influx of people have overwhelmed the capabilities of Bosnia-Herzegovina in both protecting of its own porous border with Serbia and Montenegro, but also stopping migrants from crossing over to Croatia and/or providing them with viable settlement and shelters during the transit or adjudication process. The illicit activities that enable migrations (smuggling) or seek to undermine the thin veneer of system in an otherwise heavily paralyzed country, such as Bosnia-Herzegovina have increased considerably in the last 24 months (Europol, 2019). In the latest pandemics crisis-mode, the migrants have fallen off the radar screen, but are potentially some of the most vulnerable groups and potential contagion vectors given their numbers, conditions and travel patterns.

All administrative entities of Bosnia-Herzegovina: Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (FBIH), Republic of Srpska (RS) and District of Brcko (DB) have implemented certain emergency measures related to the current pandemic, within their corresponding jurisdictions. The coherent response, on the State-level has still been relatively sluggish: Bosnia-Herzegovina was the last to close the border crossings and institute quarantining on the border, but the efficacy of it is still questionable. Even after the measure was instituted on March 18, 2020; in the last 48 hours (March 20, 2020), 9,584 citizens and 3,656 foreigners have entered Bosnia-Herzegovina apparently without much sequestration, according to the statement released by BH Border Police (Faktor.ba, 2020), suggesting that the border sealing is lax, selective at best or ineffective. Quarantine facilities have been constructed at the majority of border crossings, however the actual procedure of directing individuals to those holding facilities is still being implemented (Deutche Welle, 2020). Furthermore, RS entity is also apparently using the crisis situation to further strengthen its own administrative border and increase its autonomy within Bosnia-Herzegovina. To that effect, RS was instituting the deployment of their police forces along the checkpoints on all administrative border-crossings of RS entity in a “supportive role to the Border Police,” according to the communiqué issued on March 19, 2020 (N1-News, 2020). This activity is not passing unnoticed in the FBIH entity, especially given the heavy mobilization of military forces and military presence in Serbia and continuous appeals for Russian and Chinese aid (Simic, 2020). As of March 21, 2020, RS entity, followed by FBiH entity have instituted 8pm – 5am curfew for all citizens (N1 News, 2020), and 24-hour lockdown for those younger than 18 and older than 65 (FUCZ, 2020).

The combination of Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004, followed by the Nias earthquake, killing around 230,000 people in 14 countries and destroying much of Indonesia's Aceh province launched one of the largest humanitarian programs in history by the Indonesian government. The combined events also served as a catalyst for ending almost thirty years of military conflict between the Free Aceh Movement and the Indonesian government (Zeccola, 2010). During the martial law, Indonesian government kept Aceh closed and isolated, but the influx of foreign aid and requirement for cooperation altered the conditions on the island and allowed for the quelling of the separatist tendencies (IFIMES, 2010). However, 15 years later, political squabbling and weak governance have put Aceh back onto the downward spiral marked by sluggish development, low-level violence and intimidation, and increase in political/social dissatisfaction (TNH, 2014).

The experiences from Indonesia show that there is a certain amount of social, economic and political capital that could be invested wisely towards instigating the required change in a divided, heterogeneous community. However, the divided is easily squabbled if not immediately addressed and followed through as demonstrated in Bosnia-Herzegovina in the aftermath of floods from 2014. In 2020, the response is back to the same starting point, but this time the stakes are much higher and deadlier in a regional sense.

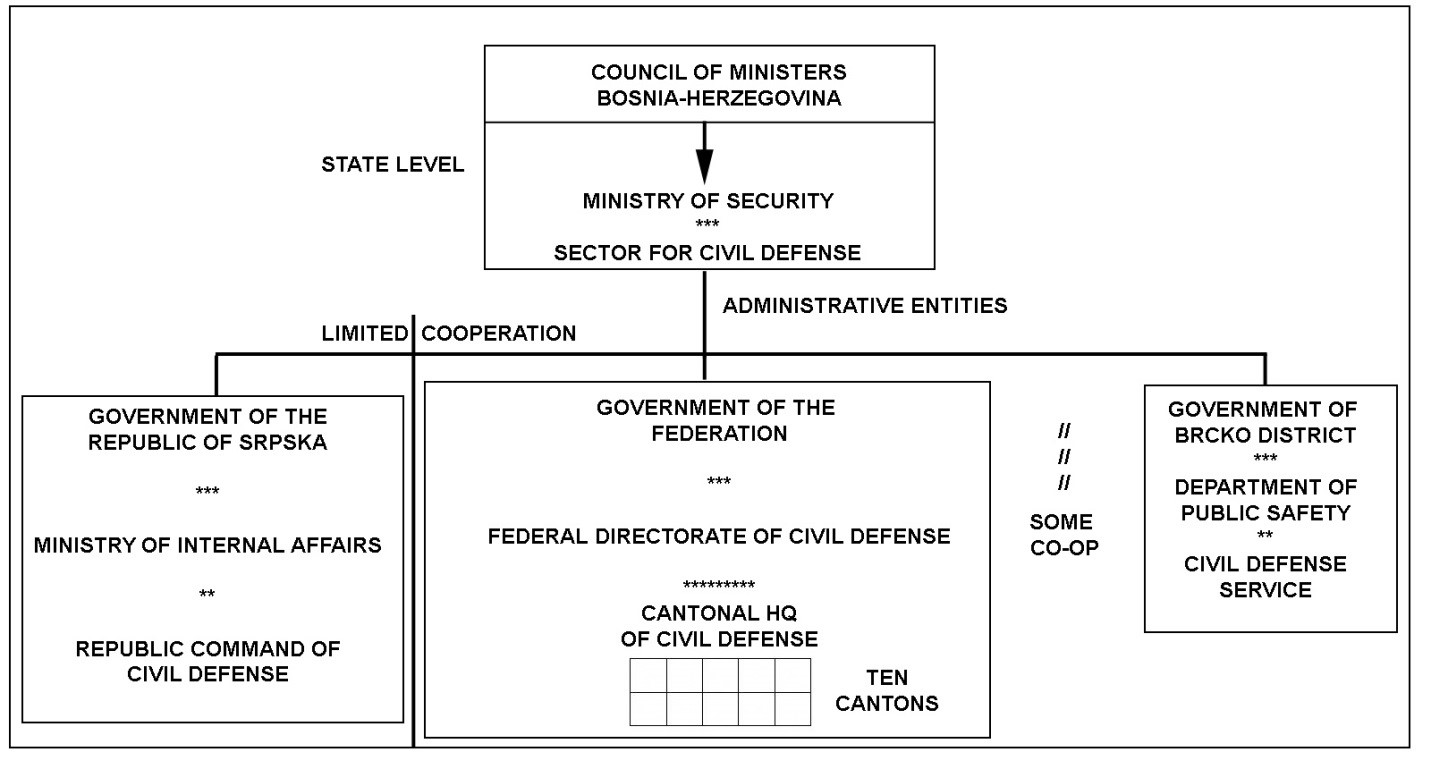

Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia present a puzzle-fit block which share a multitude of inter-linking and inter-dependent elements , but are very challenging to demarcate and separate without compromising the strategic and security considerations of all of the elements. The ongoing crisis is reinforcing that notion because the countries are watching and replicating each other’s moves and actions. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, the main administrative entities of RS and FBiH are trying to match each other’s actions and respond in kind to any implemented measures. However, there are limitations on how the individual states can exercise these activities: in a largely-centralized countries like Serbia, curfews, security forces presence and shelter-in-place lockdowns are feasible. In a decentralized environment of Bosnia-Herzegovina, particularly within FBIH entity with 10 cantons (counties), each interpreting their own policy and interest, the thankless task of coordination is placed upon the Federal Directorate of Civil Defense. Their decrees, recommendations and actions are currently the only concrete steps in crisis-communication and management on a task-force level. Their decisions are posted daily at 10am and 6pm with orders being implemented the same day. In RS entity, the decision making and recommendations are somewhat less-transparent, stemming from a more centralistic-organization of that entity (without cantons). The reader should be advised that each of the administrative regions in Bosnia-Herzegovina has its own Civil Defense directorate and in the FBIH entity, there are additional ten (10) cantonal Civil Defense headquarters – hence the level of coordination, involvement and feedback is quite daunting for such a small country.

Figure 3 – Current organization chart for Bosnia-Herzegovina civil defense sector.

Two of the largest urban-centers, Sarajevo (the State capital and administrative capital of FBH) and Banja Luka (the administrative capital of RS) have been largely effective in reducing the number of urban populace on the open, coordinating isolation, triage and care of COVID-19 positive patients and curbing the instances of price-gouging or withholding of the critical supplies etc. The effectiveness and adherence to the orders and recommendations outside of the major urban centers, is at present questionable. Many smaller communities are lacking resources to carry out the orders and recommendations, or are considering them not-applicable to their situation.

One disturbing element in the communications sphere is the uptick in unverified, false or down-right misleading information circulating through various social-media and social-communication tools (HINA, 2020). Majority of this information is alarmist or intentionally-designed to create confusion and incite panic. Even in the times of pandemic, the elements of information-warfare and narrative-generation have not disappeared in the Western Balkans (Capello & Sunter, 2018). The types of misinformation range from global conspiracy theories (intentional introduction of COVID-19) to local topics (true number of infected, closing of communications, lack of crucial medicines and “cures” for the infection).

Resulting from twenty-five years of decentralization (Congressional Research Service, 2019) Bosnia-Herzegovina (and its neighbors) has/have mustered to put their best effort forward to stop the spread of contagion. Some of the legacy institutions and procedures inherited from Yugoslavia (civil defense, communal organizations) have shown their continued benefit in the time of emergency. There is a considerable level of institutional paralysis, especially in Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the levels of cross-coordination between the different administrative entities, agencies or municipalities are significantly lacking. For example, the current natural disaster risk plan for Bosnia and Herzegovina (Federal Directorate of Civil Defense, 2014) is outlining the majority of risks that could be encountered in the Federation Entity, however it fails to address the certain realities on the ground, namely in the issues of interoperability and communication and is overly reliant on the “resources of the international community” to cover the shortcomings. A similar situation is encountered in the RS entity and very little attention is given to the interoperability and cooperation, with the majority of the responsibilities ending at the corresponding administrative border (European Commission , 2018). In order to tackle the next crisis, or a revisit of the current crisis, the administrative entities of Bosnia-Herzegovina and the neighboring countries will have to establish a joint nexus to re-start the cooperation and communication on even terms, perhaps by using their still-functioning legacy solutions. The region does not have a luxury to squander yet another opportunity like it did in 2014 to form a coherent, unified emergency response service. It is still not clear how and if Bosnia-Herzegovina and Western Balkans will emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic and whether their hastily-assembled organization will hold the contagion at the manageable levels. The crisis does illustrate that more transparency, more communication and less political posturing are required to address the evolving situation on the ground, especially when the international community is occupied with its own problems. The crisis also may haste the demise of Bosnia-Herzegovina as a functional state and result towards establishment of new geopolitical realities in the Western Balkans.

Other crisis research at FCCSS (pathways to future cooperation)

Faculty of the Criminology, Criminalistics and Security Studies at the University of Sarajevo, in cooperation with its partners from the region and United States of America have been working on several possible venues for cross-border cooperation in the areas of crisis-response and crisis-communication (Kesetovic & others, 2013). Some of the key-point areas of interest are:

What all of these scenarios have in common is the ongoing requirement for clear, concise and effective communication across the complex regional political spectrum. Some of the potential crisis-response scenarios and initiatives can be hindered by ineffective, incomplete or overly-bureaucratic / overly-politically-colored communication and sometimes it takes a crisis to open other possible venues of cooperation.

About the authors:

Amer Smailbegovic holds a Ph.D. degree from the University of Nevada, USA, (2002) in the subject area of remote sensing and signal processing. His activity is mainly in the private sector with the emphasis on the projects related to aerospace-defense, geospatial data-integration and emergency response. He is currently based in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina and provides advisory services on demilitarization, crisis-management and energy security.

Nedzad Korajlic holds a Ph.D. degree from the University of Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina (2006) in the area of criminalistics and criminal justice. He is currently serving as the Dean of the Faculty of Criminalistics, Criminology and Security Studies at the University of Sarajevo. His past tenure includes Academia, with textbooks on forensics, crisis management, criminology and almost 15 years of active Law-Enforcement in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Ljubljana/Sarajevo, 25 March 2020